Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera weren’t the only ones trying to make it in the TV cartoon business in 1957, but they were the most successful. Everything fell into place for them. They needed a bankroller. They found one in Columbia Pictures, thanks to intermediary George Sidney (who got a piece of the action for hooking up the two with the studio. They figured out a way to make limited animation look less limited than Crusader Rabbit and made-for-television cartoons of the day, and do it affordably. And they came up with likeable characters, who they put in entertaining situations. The end result? Sponsors, viewers, critical praise and people buying merchandise. All that equalled, as Fred Flintstone later remarked, “Do-Re-Mi Money.”

Hanna-Barbera’s success attracted attention in the trade press. Actually, the trades had been commenting on trends in animation for some time. What a difference a decade made. At the start of the 1950s, stories basically stated theatres saw no value in running cartoons and studios couldn’t make a profit on new ones. But then came expansion of television. Television needed programming. Old theatrical cartoons were sitting on the shelf, virtually worthless to the studios. The broadcast rights were sold to distributors—movie studios weren’t going to dirty themselves in something as mediocre as television, even if they had the mechanism—who proceeded to rake in small fortunes. Better and more desirable cartoons came on the market as the decade wore on, climaxing in two deals by AAP, one in early March 1956 to acquire pre-1948 Warner Bros. colour cartoons, and another about seven weeks to pick up 234 Popeye cartoons from King Features and Paramount (Billboard, Apr. 21, 1956). The airwaves became flooded with Bugs Bunny and Olive Oyl’s boyfriend as station after station after station eagerly snapped up the top-notch animated shorts. Having just about run out of old theatricals to put on TV, the idea of made-for-TV cartoons gained new traction. And that’s when Bill and Joe enter the story.

Originally, Bill and his brother-in-law, Mike Lah, were hired to create new Crusader Rabbit cartoons. But through some legal slight-of-hand, the project was forced off the drawing boards. Hanna, Barbera and Lah then borrowed the Crusader continuing-adventure format, plugged some new characters into it, and Ruff and Reddy were born.

Television Age magazine picks up the rest of the story for us, the story up until March 7, 1960, when the following was published. What’s great about this spotlight piece is not only were the Flintstones still into their “Flagstones” stage, but it’s the only publication I’ve found with a model drawing of Fred, Jr. You all know the character was dropped in development, and I can only presume it’s because Hanna and Barbera wanted a show based around the adults (Honeymooners, anyone?) and not a family. Of course, Ideal Toys’ bank account changed that later. Fred Jr. has the exact same design as Ubble Ubble from the Ruff and Reddy cartoons; Bill and Joe weren’t above borrowing from themselves (something that became all too apparent as the studio rolled on).■ ■ ■

Cartoon comeback

With planned technique and original story lines . . . Hanna-Barbera Productions gives animation new lifeOnce upon a time Joe Barbera went out to the wonderful land of Hollywood to make cartoons. He worked very hard and was immensely gratified when theatregoers across the nation squealed like mice to see his Tom and Jerry run. A proud man, he would quietly observe that his output. eight seven -minute cartoons a year. was a heavy one. Then, one day, the pencil dropped. the ink dried: from high up in the tinselly towers of that mysterious world came a cry, echoing and re-echoing through the empty lots, the quiet streets, the vacant minds: enough! No more! And Joe Barbera, a storyteller without an audience, looked at his friend, Bill Hanna, an artist without a canvas, and they were both sad.

That was in 1957. If Mr. Barbera, partner in Hanna-Barbera Productions, Inc., looks at the past as though it were an especially poignant fairy tale, he has a right to, for the ending is in the best tradition of those narratives: the two protagonists lived busily ever after. As producers of

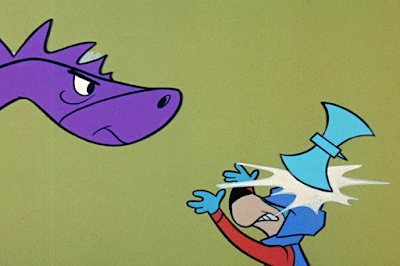

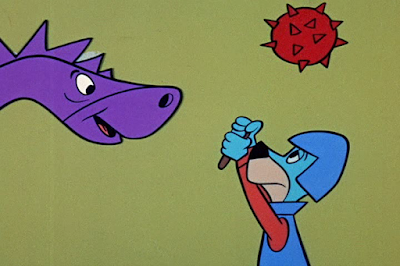

Ruff & Reddy, Huckleberry Hound, Quick Draw McGraw and

The Flagstones (which is scheduled for prime evening time over ABC-TV next season), Hanna-Barbera is nothing if not busy. Today the company can be considered the leading producer of new cartoons for television, an occupation which was considered irresponsible or worse a few years ago by the hardheaded, the extremely hardheaded businessmen of that era. It didn't make economic sense, they argued, good animation is too expensive. limited animation too shoddy.

![]()

In developing a technique which was both good and economical the partners did to cartooning what the European small cars did to Detroit: initiated a minor revolution. That technique, called “planned animation” by Mr. Barbera, involves employing a rare commodity—experience—in the day-to-day operation. In his words, “you have to know when to cut and when not to cut. It's as simple as that. Limited animation is a mistake. Some people think they can save money and still come up with something good by taking cut-outs and moving them around a fixed background. It isn't that easy.”

Planned animation caught on quickly. With Screen Gems acting as distributor,

Ruff & Reddy, a story about a frisky cat and a dim-witted dog, went on the air over NBC -TV in 1957.

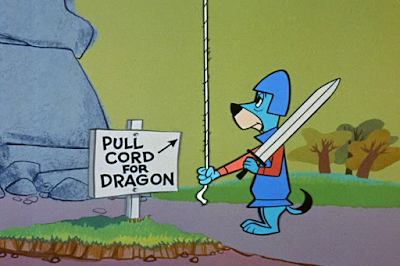

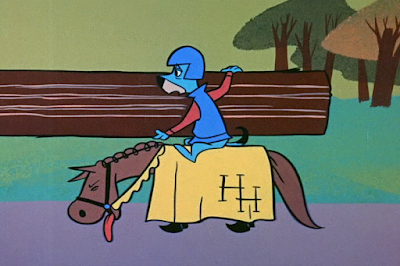

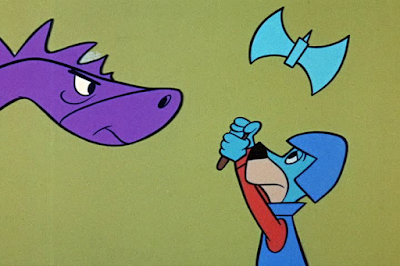

Huckleberry Hound, the saga of a canine Don Quixote, was picked up by Kellogg's in a huge national spot spread in 1958, and was recently renewed.

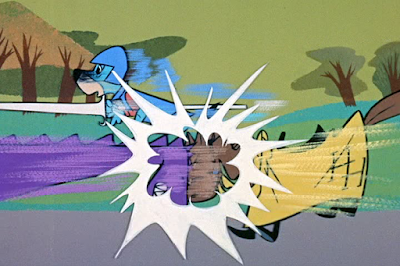

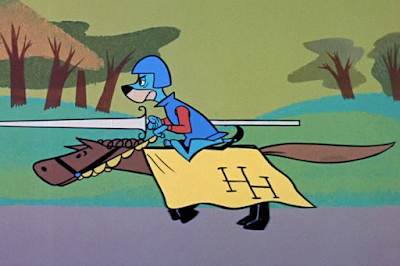

Quick Draw McGraw, which is about an obtuse horse and his more perceptive, Spanish-speaking burro sidekick, was purchased by Kellogg's last year as part of its national spot pattern. Just last month ABC-TV purchased

The Flagstones, a satire on an exurbanite family in the Stone Age. The historical background is irresponsibly recreated.

To make the cartoon-comeback circle complete, H-B has re-entered the theatrical-cartoon field—using its television technique. The company has signed a five -year exclusive contract with Columbia Pictures, parent company of Screen Gems. First theatrical cartoon series has been titled

Loopy De Loop.If the concept of planned animation seems unnecessarily vague in that it is basically a common-sense approach to production problems, its execution is another matter. Mr. Barbera is a story man and artist, and Mr. Hanna is a technician. With this start, a technique was worked out whereby all cartoon story men have learned to draw well enough to do their scripts in sketch form. “If the scripts were typed up we'd have to call in a sketch man and in the last analysis end up with a compromise,” Mr. Barbera observes. A certain amount of freshness and spontaneity is preserved this way, and the savings in time and cost are obvious, he notes.

Production is maintained at all times, and to avoid slowdowns an open -door policy is in effect at the shop (the Amco studios in Hollywood).

“We have no executives here. Everyone is available, and everyone works. We make quick decisions: if a story man comes in with an idea he gets a yes or no, frequently within a matter of minutes.”

H-B's production schedule demands this kind of concentration. Mr. Hanna and Mr. Barbera once did eight cartoons a year for theatrical release, and were proud of it. Today they do four cartoons a week for television, and all of them are in color. Another comparison: in 20 years of work for MGM the team turned out 120

Tom and Jerry cartoons; in two years in television they produced over 300 cartoons, and have orders totaling 700.

Planned animation affords a savings of about half over full animation, says Mr. Barbera. Where the latter utilizes as much as 17,000 cels (individual pictorial units) in a seven-minute cartoon, only 1,000 to 2,000 are used in planned animation for the same length production, and for the same or greater number of scenes and characters. This, in turn, has attracted business: in its first full year of operation (1958) H-B grossed $1 million; in 1959 the figure more than doubled to $2.25 million; in 1960, current contracts guarantee a gross of at least $3 million.

Curiously, the whole concept of planned animation grew out the studios of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. There, a technique was developed whereby a projected cartoon was done roughly at first, as a kind of preview. Mr. Barbera animated and drew and then broke the pictures into scenes, while Mr. Hanna timed it out. If it was found acceptable, a full cartoon was made. When MGM discontinued production of new cartoons, the partners took their wares elsewhere, convinced that a refinement of the preview technique could be adapted for television, and for motion-picture theatres, for that matter. Screen Gems, a partner in anything it finances of H-B's, agreed to distribute the product.

Affable and relaxed, Mr. Barbera is something of a salesman himself. He has a contagious regard for the numerous characters he has created, and a good ear for inflections and intonations of speech. These qualities helped him sell

Huckleberry Hound to the Leo Burnett people (for Kellogg's) with just three storyboards, and before the character of Huckleberry Hound had been created. (Initially, the program consisted of Yogi Bear, Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinx.) [sic] That was on July 7, 1957, exactly 20 years to the day he started with MGM.

An emphasis on the purely technical aspects of the company's operation does not begin to explain its success. Mr. Barbera is quick to point out that “we can have the best staff in the world, but without story, characters, proper timing, we're doomed.”

The approach to the cartoons, however, is what seems to distinguish H-B Productions from its competitors. It has been described as light satirization, or wholesome burlesques, of familiar situations. It is largely a civilized humor which has caught on with children, and with many adults. Although violence is used on occasion to right wrongs, there is no sadism, little of the prat-fall humor which characterizes many of Hollywood's cartoons. With this tenuous formula, Messrs. Hanna and Barbera can be expected to make a major contribution to children's programming, and a modest one to adult fare.

■ ■ ■

Those last two paragraphs sum up why the early Hanna-Barbera cartoons have such appeal today.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()