When you think of Hanna-Barbera and music, you probably think of Hoyt Curtin and those terrific background pieces he wrote for Jonny Quest and Top Cat. Personally, I also think of those great stock music libraries written for (or released by) the Capitol Hi-Q and Langlois Filmusic series heard in the earliest cartoons. You likely don’t think of the Hogs. Or the Guilloteens. Or the Thirteenth Floor Elevators. But you should.

All three were among the bands signed in the mid-60s to contracts with Hanna-Barbera Records.

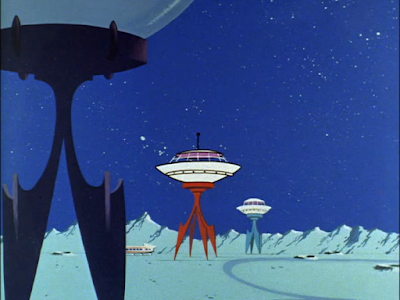

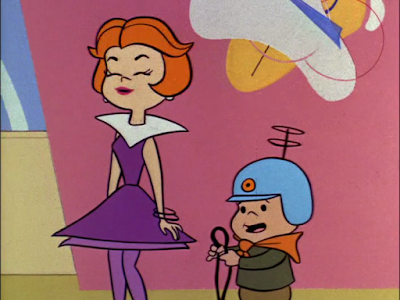

Yes, in late 1964, while Jonny Quest was teetering on the brink of prime-time cancellation and Secret Squirrel and Atom Ant were in development, Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera decided to get into the record business.

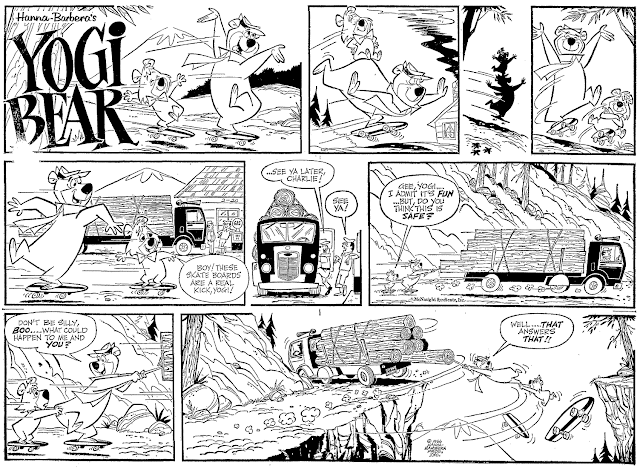

Bill and Joe had been somewhat involved with record labels before. Golden Records in New York had produced and released knock-offs of Hanna-Barbera cartoon themes (and a few other songs based on characters to fill out the sides). And Colpix, Columbia Pictures’ TV music arm, released some cartoon soundtracks (minus the Hi-Q music for contractual reasons) and characters narrating stories. But this was different. The company created a subsidiary to release its own artists. And we don’t mean Daws Butler singing as Wally Gator.

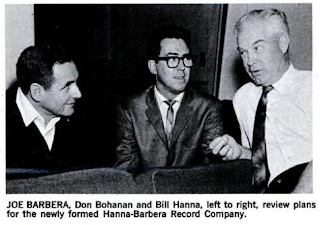

Neither Hanna nor Barbera (unless I missed it) talked about the short-lived venture in their autobiographies, leaving it up to others to explain why they got into music business. Billboard in its issue of January 15, 1965 stated it stemmed from the cartoon producers’ belief “that the promotional sales value of records had hardly been tapped.” The story quoted Don Bohanan, the head of the brand-new subsidiary, that the division not only wanted to release “a powerful children’s line” but “develop strong representation in the popular music field.” And since it was 1965, pop music was starting to change from the yeah-yeah-yeah “bug music,” as it was satirically called on The Flintstones. That meant garage rock and psychedelia, and that’s what Hanna-Barbera Records got into, as Bohanan promised the label “intended to release a minimum of 20 LP’s and 50 to 70 singles a year in the pop music.” The wonderful Spectropop site has more on some of the rather odd releases.

(Billboard reported on December 24, 1964 that since November 1963, Bohanon had been marketing director at Liberty Records, the label that brought you the Chipmunks, and had started with Coral Records around 1954).

What happened to Hanna-Barbera Records? The same thing that happened to Hanna-Barbera Productions. It was officially sold to Taft Broadcasting on December 28, 1966. Within a month a decision was made to have to have any record product concentrate solely on cross-promoting cartoons. The days of a separate subsidiary were done. The company gave up its independent distribution set-up. Bohanan quit (Billboard, May 13, 1967) and by the following December, Paul DeKorte was named supervisor of production for children’s records under Hanna-Barbera Productions, released by the Sunset Records arm of Liberty.

More than 8½ years ago, Kliph Nesteroff wrote a pretty detailed treatise on Hanna-Barbera Records which you can read HERE. You’d figure nothing else was left to be said. But no! Now that Kliph has finished uncovering the sex, drugs and rock-and-roll of stand-up comedy in his new book The Comedians, he’s turning his attention back to Hanna-Barbera Records. Did he dredge up more sex, drugs and rock-and-roll in his research? Well, we know he found the last of the three. And Kliph’s pretty thorough in his interviews and other research, so you can bet he found a lot of other things. He has written a five-thousand word article which, we hope, may be the prelude to another book. You can go to his fine blog site and read about it.

All three were among the bands signed in the mid-60s to contracts with Hanna-Barbera Records.

Yes, in late 1964, while Jonny Quest was teetering on the brink of prime-time cancellation and Secret Squirrel and Atom Ant were in development, Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera decided to get into the record business.

Bill and Joe had been somewhat involved with record labels before. Golden Records in New York had produced and released knock-offs of Hanna-Barbera cartoon themes (and a few other songs based on characters to fill out the sides). And Colpix, Columbia Pictures’ TV music arm, released some cartoon soundtracks (minus the Hi-Q music for contractual reasons) and characters narrating stories. But this was different. The company created a subsidiary to release its own artists. And we don’t mean Daws Butler singing as Wally Gator.

Neither Hanna nor Barbera (unless I missed it) talked about the short-lived venture in their autobiographies, leaving it up to others to explain why they got into music business. Billboard in its issue of January 15, 1965 stated it stemmed from the cartoon producers’ belief “that the promotional sales value of records had hardly been tapped.” The story quoted Don Bohanan, the head of the brand-new subsidiary, that the division not only wanted to release “a powerful children’s line” but “develop strong representation in the popular music field.” And since it was 1965, pop music was starting to change from the yeah-yeah-yeah “bug music,” as it was satirically called on The Flintstones. That meant garage rock and psychedelia, and that’s what Hanna-Barbera Records got into, as Bohanan promised the label “intended to release a minimum of 20 LP’s and 50 to 70 singles a year in the pop music.” The wonderful Spectropop site has more on some of the rather odd releases.

(Billboard reported on December 24, 1964 that since November 1963, Bohanon had been marketing director at Liberty Records, the label that brought you the Chipmunks, and had started with Coral Records around 1954).

What happened to Hanna-Barbera Records? The same thing that happened to Hanna-Barbera Productions. It was officially sold to Taft Broadcasting on December 28, 1966. Within a month a decision was made to have to have any record product concentrate solely on cross-promoting cartoons. The days of a separate subsidiary were done. The company gave up its independent distribution set-up. Bohanan quit (Billboard, May 13, 1967) and by the following December, Paul DeKorte was named supervisor of production for children’s records under Hanna-Barbera Productions, released by the Sunset Records arm of Liberty.

More than 8½ years ago, Kliph Nesteroff wrote a pretty detailed treatise on Hanna-Barbera Records which you can read HERE. You’d figure nothing else was left to be said. But no! Now that Kliph has finished uncovering the sex, drugs and rock-and-roll of stand-up comedy in his new book The Comedians, he’s turning his attention back to Hanna-Barbera Records. Did he dredge up more sex, drugs and rock-and-roll in his research? Well, we know he found the last of the three. And Kliph’s pretty thorough in his interviews and other research, so you can bet he found a lot of other things. He has written a five-thousand word article which, we hope, may be the prelude to another book. You can go to his fine blog site and read about it.