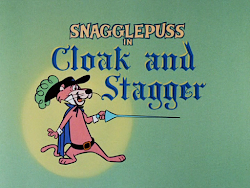

Produced and Directed by Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera.

Credits: Animation – Don Patterson, Layout – Jack Huber, Backgrounds – Fernando Montealegre, Written by Mike Maltese, Story Director – Paul Sommer, Titles – Art Goble, Production Supervision – Howard Hanson.

Voice Cast: Snagglepuss, Prof. Cageo – Daws Butler; Ringmaster, Ape, Ape Baby, Tarzanish guy – Don Messick.

Music: Hoyt Curtin.

Copyright 1961 Hanna-Barbera Productions.

Plot: Snagglepuss escapes from the circus to the jungle, where he realises that circus life wasn’t so bad.

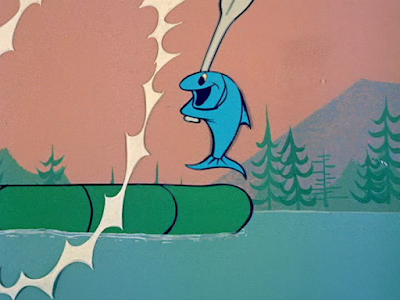

Before we get to old Snagglepuss, let’s show off some of Monty’s backgrounds. First, some circus drawings, including the shot to open the cartoon.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Now, some jungle scenes.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The premise that became Wally Gator is what drives this cartoon. Snagglepuss is a circus performer. He’s unhappy. All he does is take clichéd orders from a lion tamer. (“Hmmm. Changed his hair tonic again,” observes the unhappy Snagglepuss after Professor Cage-o puts his head in his mouth). So he quits and heads by ship to the ancestral home of lions—the jungle. Yes, I know Snagglepuss is amountain lion, thus not native to Africa, but why spoil the plot?

Anyway, you know what’s going to happen. After all, the Snagglepuss series can’t just move to Africa. He finds the jungle is a worse experience than the circus. First, natives throw arrows at him (we don’t see the natives, thus eliminating pontification by cartoon fans about racism). He escapes by climbing a tree, which turns out to be a giraffe that slings him into a lake with floating suitcases. Only they turn out to be alligators (“Exit, not unpackin’, stage left!”). He escapes again by running off camera and into a large ape.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The large ape picks up Snagglepuss to give to his baby (wearing a bonnet, even in the jungle) as a toy. First, Snagglepuss is involuntarily turned into a doll that squeaks “Mama” when you poke its stomach, then a wind-up toy.

The large ape picks up Snagglepuss to give to his baby (wearing a bonnet, even in the jungle) as a toy. First, Snagglepuss is involuntarily turned into a doll that squeaks “Mama” when you poke its stomach, then a wind-up toy.

![]()

![]()

The story takes a turn when a Tarzan-like guy swings into the scene, announces he is the king of beasts, and Snagglepuss is an “oomba-oomba,” in other words, a lion-skin rug (“Heavens to floormat!”) which Tarz is about to skin. “Exit, beatin’ a rug to safety, stage right! cries Snagglepuss. Back he goes to the comparative safety of the circus, content to be shot out of a cannon, to end the cartoon.

![]()

![]()

Don Patterson animates this cartoon. He gives Snagglepuss expressions that aren’t wild, but effective such as the look of disgust when he’s forced to obey the lion tamer’s commands. His mid-air run cycle is used three times in the cartoon; Patterson has Snagglepuss facing one way while his arms are pointed in the other direction.

Don Messick voices all but one of the incidental characters because he can.

The opening circus scenes feature the Hoyt Curtin version of “Man on the Flying Trapeze” and during the Tarzan-guy swinging scene, he uses that short Flintstones cue that samples two bars of Fucik’s “Entry of the Gladiators.” (Look it up. You’ll go “Oh, that’s what that’s called.”).

Maltese loads up on catch-phrases in this cartoon, though he eschews “Murgatroyd.” Cashews, even. How about almonds? Peanuts, popcorn, Cracker Jacks, even? Exit this post, nutty all the way, stage left.

Credits: Animation – Don Patterson, Layout – Jack Huber, Backgrounds – Fernando Montealegre, Written by Mike Maltese, Story Director – Paul Sommer, Titles – Art Goble, Production Supervision – Howard Hanson.

Voice Cast: Snagglepuss, Prof. Cageo – Daws Butler; Ringmaster, Ape, Ape Baby, Tarzanish guy – Don Messick.

Music: Hoyt Curtin.

Copyright 1961 Hanna-Barbera Productions.

Plot: Snagglepuss escapes from the circus to the jungle, where he realises that circus life wasn’t so bad.

Before we get to old Snagglepuss, let’s show off some of Monty’s backgrounds. First, some circus drawings, including the shot to open the cartoon.

Now, some jungle scenes.

The premise that became Wally Gator is what drives this cartoon. Snagglepuss is a circus performer. He’s unhappy. All he does is take clichéd orders from a lion tamer. (“Hmmm. Changed his hair tonic again,” observes the unhappy Snagglepuss after Professor Cage-o puts his head in his mouth). So he quits and heads by ship to the ancestral home of lions—the jungle. Yes, I know Snagglepuss is amountain lion, thus not native to Africa, but why spoil the plot?

Anyway, you know what’s going to happen. After all, the Snagglepuss series can’t just move to Africa. He finds the jungle is a worse experience than the circus. First, natives throw arrows at him (we don’t see the natives, thus eliminating pontification by cartoon fans about racism). He escapes by climbing a tree, which turns out to be a giraffe that slings him into a lake with floating suitcases. Only they turn out to be alligators (“Exit, not unpackin’, stage left!”). He escapes again by running off camera and into a large ape.

Snag: I realise you don’t realise that with which to whom you are dealin’. To wit.

Ape: Rumpff?

Snag: I’ll give you a hint. Roooaaaar! Get it? King of the beasts. You may flee in sheer terror if you so desire.

Ape: Raaarrr.

Snag: Duke of the beasts. Count of the beasts? Beauty and the beasts, even.

Ape: RaaAAArr!

Snag: How’s about an ordinary, everyday type citizen? Can I take out my first citizenship papers?

Ape: RaaAAArrrr!

Snag: Would object to my getting’ a driver’s license? A library card, even.

The large ape picks up Snagglepuss to give to his baby (wearing a bonnet, even in the jungle) as a toy. First, Snagglepuss is involuntarily turned into a doll that squeaks “Mama” when you poke its stomach, then a wind-up toy.

The large ape picks up Snagglepuss to give to his baby (wearing a bonnet, even in the jungle) as a toy. First, Snagglepuss is involuntarily turned into a doll that squeaks “Mama” when you poke its stomach, then a wind-up toy.

The story takes a turn when a Tarzan-like guy swings into the scene, announces he is the king of beasts, and Snagglepuss is an “oomba-oomba,” in other words, a lion-skin rug (“Heavens to floormat!”) which Tarz is about to skin. “Exit, beatin’ a rug to safety, stage right! cries Snagglepuss. Back he goes to the comparative safety of the circus, content to be shot out of a cannon, to end the cartoon.

Don Patterson animates this cartoon. He gives Snagglepuss expressions that aren’t wild, but effective such as the look of disgust when he’s forced to obey the lion tamer’s commands. His mid-air run cycle is used three times in the cartoon; Patterson has Snagglepuss facing one way while his arms are pointed in the other direction.

Don Messick voices all but one of the incidental characters because he can.

The opening circus scenes feature the Hoyt Curtin version of “Man on the Flying Trapeze” and during the Tarzan-guy swinging scene, he uses that short Flintstones cue that samples two bars of Fucik’s “Entry of the Gladiators.” (Look it up. You’ll go “Oh, that’s what that’s called.”).

Maltese loads up on catch-phrases in this cartoon, though he eschews “Murgatroyd.” Cashews, even. How about almonds? Peanuts, popcorn, Cracker Jacks, even? Exit this post, nutty all the way, stage left.