![]() This year (as of July 7th) marks the 65th birthday of H-B Enterprises. The studio only had one main accomplishment in 1957—it convinced Columbia Pictures’ Screen Gems division to put up the money for a TV cartoon series, which the studio then convinced NBC to broadcast on Saturday mornings.

This year (as of July 7th) marks the 65th birthday of H-B Enterprises. The studio only had one main accomplishment in 1957—it convinced Columbia Pictures’ Screen Gems division to put up the money for a TV cartoon series, which the studio then convinced NBC to broadcast on Saturday mornings.

Weekend programming back then was not a huge priority for networks, so NBC had no qualms about tossing Ruff and Reddy onto the schedule after the start of the season. It debuted in December. The second and third seasons began in subsequent Falls.

The first two 13-part adventures to open the series’ third season on Saturday morning, October 17, 195912 were copyrighted in September the previous year (Series ‘L’, Dizzy Deputies; Series ‘M’, Spooky Meeting at Spooky Rock). Presumably, they had already been finished and were sitting in cans at 1416 La Brea Avenue awaiting shipment to NBC.

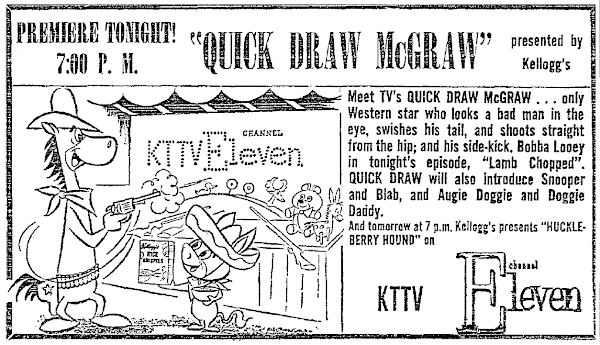

The final two 13-parters were copyrighted on September 15, 1959 (Series ‘N’, Sky High Guys; Series ‘O’, Misguided Missile). By that time, Hanna-Barbera had hired additional artists to handle the load of the new Quick Draw McGraw Show and the theatrical Loopy De Loop cartoons. Also, writer Charlie Shows left in November 1958 to work for Larry Harmon, who was ready to make a series of Bozo the Clown cartoons for syndication.

The first of the 1959-made episodes was “Sky High Guys” (debuting February 12, 19603) began with our heroes accidentally taking off in a balloon at a county fair and ending up on a desert island trying to stop two crooks (Captain Greedy and Salt Water Daffy) from stealing a treasure chest from Skipper Kipper and his parrot Squawky Talky.

13 cartoons is a little much for one animator to handle, and I’ve been able to identify two of them. Carlo Vinci starts off the series. You can spot him again in “Tiff on a Skiff.” Captain Greedy has a bar of upper teeth. Reddy doesn’t zip out of the scene in a diving exit; he uses a curved back exit that Carlo drew for other characters like Huckleberry Hound and Fred Flintstone. And he also has a particular angle he draws a straight leg with the foot up almost at a 90-degree angle. You can see this in other cartoons.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Two episodes later, in “Squawky No Talky,” there’s a different animator. Add up the signs. The bit lip on the letter “f” and individual upper teeth. He animated Fred Flintstone the same way.

![]()

The almost double isosceles triangle closed eyes.

![]()

The up-and-down dip walk with no legs. He animated Ranger Smith this way in “Bewitched Bear.” I’ve slowed down the walk in the animated .gif below. And it’s missing a number of frames because of ghosting on the internet dub of the cartoon, but you get the idea. It’s animated on ones.

![]()

The animation is by Don Patterson, who joined the Hanna-Barbera staff from Walter Lantz in April 1959. Patterson was unemployed and looking for work according to the U.S. Census taken April 29, 1950. He arrived at Lantz later in the year, animated for a bit, was made a director in 1952 and stopped directing in 1954. He was moved back into full-time animating. His Woody Woodpecker animation includes some great exaggerated takes. I get the impression that as the ‘50s progressed, studios decided wildness was passé and cartoons got tamer and tamer.

Here’s a Patterson take from “Squawky No Talky.” It’s not all that outrageous, even compared with his work at Lantz, but it’s not what you’d expect in a Hanna-Barbera cartoon. You think George Jetson was ever animated this way?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

It appears H-B Enterprises loved airbrushed action. Here’s some (with multiples) in a later scene.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For Patterson, as well as some of the other earliest Hanna-Barbera artists, dialogue wasn’t just a mouth or lower part of a jaw moving with everything else rigid. In the scene below, Patterson uses three head positions. The middle drawing is used whenever certain vowels are spoken. The other two positions have the mouth open and close. Bill Hanna’s timing is such that the head moves on ones, two and threes; the in-betweens aren’t the same number, which would make the animation look mechanical.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Because Charlie Shows was gone from Hanna-Barbera in November 1958, I don’t suspect he worked on this episode. If I had to guess, I think Mike Maltese may have had a hand in this. At one point (in “Tail of a Sail in a Whale”), Daffy says “I’m doin’ the diggin’, and don’t forget it,” reminiscent of Quick Draw McGraw’s “thinnin’” line to Baba Looey. And pardon my sloppy research here as I don’t recall if it’s on this adventure, but there are a couple of times where the narrator talks to the characters, which just seems like a Maltese thing.

I’m not sure about all 13 parts of this storyline, but it looks like Bob Gentle provided at least some of the backgrounds. Today’s trivia: though they graduated 3 ½ years apart, Patterson and Gentle attended Hollywood High School at the same time for a brief period (photos below are from the same page of the 1927 annual).

![]()

A final note about “Squawky No Talky,” I’d love to do a breakdown of the music, but I don’t recognise any of the music in it. It’s obviously from the same two libraries that were used in Hanna-Barbera’s other cartoons at the time, but these particular cues were exclusive to Ruff and Reddy. I don’t have a complete collection of the Capitol Hi-Q “D” series and I’m pretty sure some music that sounds like Spencer Moore’s in this cartoon comes from one of the missing discs. The second last cue, when Daffy is threatening Squawky, sounds like a Loose-Seely dramatic melody while final cue, when Daffy is being attacked by the parrot, is another of Jack Shaindlin’s sports marches. There is some familiar Moore, Loose-Seely and Phil Green music in other parts of the adventure. The last season of Ruff and Reddy seems to use a lot more music than the first one, which were content with two or three different pieces (saving time and money in editing).

Patterson was still working at Hanna-Barbera decades later, credited as an animation director on The Flintstone Kids (1988), a good 55 years after assistant animating at the Charles Mintz studio (a look at the end credits reveals a wealth of veterans, including Patterson’s younger brother Ray, and Art Davis who went back to the ‘20s at Fleischers).

Donald William Patterson was born in Chicago on December 26, 1909. After Mintz, he stopped at Disney and MGM before Walter Lantz gave him a job. He died in Santa Barbera, California on December 12, 1998. (He is pictured to the right with Lantz in front of the storyboard for Operation Sawdust).

1 Fort-Worth Star-Telegram, Oct. 17, 1959, pg. 18. See also Feb. 6, 1960, pg. 6↩

2 KMJ, Fresno, broadcast the show at 5:15 p.m. on Fridays. KERO, Bakersfield, also an NBC station, aired it on Saturdays at 9 a.m.↩

3 El Paso Times, Feb. 13, 1960, pg. 8. See also Feb. 6, 1960, pg. 6↩

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()